Very low incomes for Indigenous artists and other workers in the arts and culture

Analysis of the incomes of artists, arts leaders, and all cultural workers, including differences by gender

Today’s post analyses the median incomes of Indigenous men and women within four broad groupings of occupations: artists, arts leaders, workers in cultural occupations, and all Canadian workers. (The cultural workers grouping includes artists and arts leadership occupations, as well as many other occupation groups.)

It follows a recent post showing that the representation of Indigenous Peoples is lower among arts leaders (2.7%) and cultural workers (3.0%) than artists (3.7%), and slightly lower among artists than all workers (4.2%). In the census, Indigenous identity is based on self-identification as First Nations, Métis, and/or Inuit.

The post examines income statistics for artists as a group, for arts leaders as a group, and for cultural occupations as a group – not for individual occupation categories (e.g., craftspeople, actors, curators, arts managers, etc.). The income statistics from the 2021 census relate to 2020, a year with many pandemic lockdowns and slowdowns in artistic activity. My focus is on median personal income, which includes all sources of income, including (for example) employment income and pandemic supports.

Details of the census questions and occupational categories, as well as other notes regarding methods, are provided at the end of this post.

This high-level summary of the situation of Indigenous artists, arts leaders, and cultural workers examines Indigenous workers as a group, rather than exploring differences arising from the diversity of Indigenous Peoples residing on the territory commonly known as Canada. In addition, the post highlights gender differences, but these are not explored in significant detail.

Context: Indigenous workers have lower incomes in general, and women’s incomes are lower than men’s

Among all workers in Canada, Indigenous women have the lowest median incomes. Indigenous men have somewhat higher median incomes, which are essentially equal to the median incomes of non-Indigenous women. Non-Indigenous men have by far the highest median personal incomes. More specifically as shown in the graph below:

Non-Indigenous men have a median income of $54,800.

Non Indigenous women have a median income of $45,600, 17% lower than non-Indigenous men.

Indigenous men have a median income of $46,000, 16% lower than non-Indigenous men.

Indigenous women have a median income of $43,200, or 21% lower than non-Indigenous men.

The rest of this post analyses the median incomes of artists, arts leaders, and workers in cultural occupations, with comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous women and men in these positions.

I want to state that I’m not happy to place this post on the incomes of Indigenous artists and cultural workers behind a paywall. However, paid subscribers are my only source of funding for these reports, and I have to provide value added for them.

Incomes are much lower for Indigenous than non-Indigenous artists and arts leaders

For artists, as shown in the graph below:

Non-Indigenous men have the highest median income ($32,800).

Non-Indigenous women have median income of $28,800, 12% lower than non-Indigenous men.

For the 3,200 Indigenous men artists, the median income is $26,200, 20% lower than non-Indigenous men.

For the 4,200 Indigenous women artists, the median income is $27,200, 17% lower than non-Indigenous men. (Note that there is a very small difference in incomes between Indigenous women and men.)

Among artists, there is a significant income gap between non-Indigenous men and others. Broadly speaking, these gaps are similar to the differences in the overall economy.

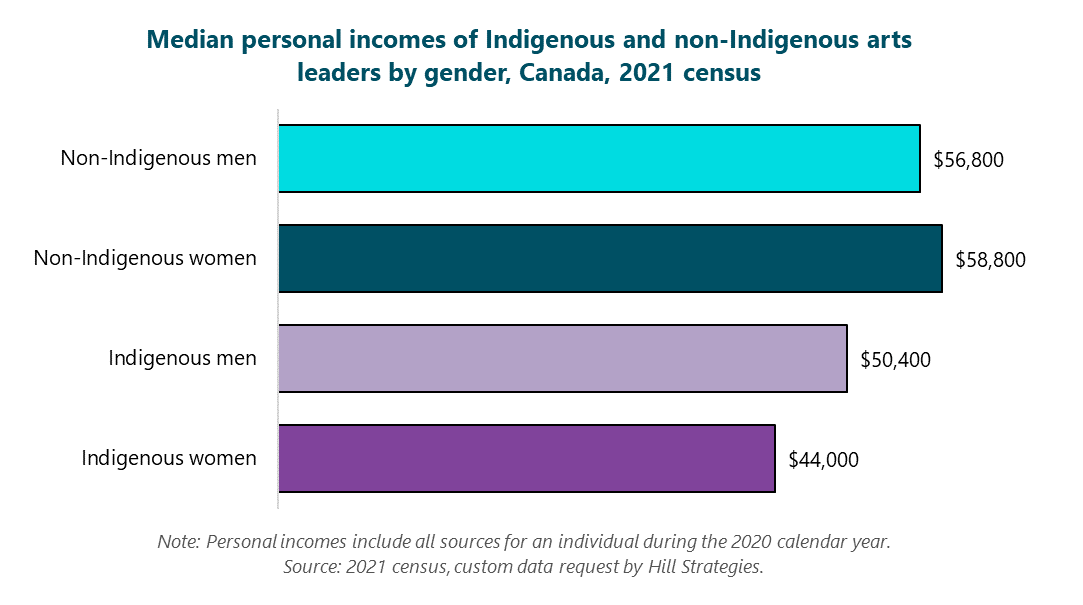

Arts leadership occupations

The graph below shows that, among arts leaders:

The median personal income is slightly higher for non-Indigenous women ($58,800) than non-Indigenous men ($56,800) who work in one of five arts leadership occupation groups.

The 810 Indigenous men who work in the arts leadership occupation groups have a median income of $50,400, 11% lower than non-Indigenous men.

The 710 Indigenous women who work in the arts leadership occupation groups have a median income of $44,000, 23% lower than non-Indigenous men.

Similar findings among cultural workers: Incomes are much lower for Indigenous than non-Indigenous workers

There is a substantial income gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultural workers, although there is almost no difference between Indigenous women and Indigenous men.

As depicted in the graph below, among workers in all 52 occupation groups in the arts, culture, and heritage:

Non-Indigenous men have the highest median income ($50,000).

Non-Indigenous women have a median income of $44,000, 12% lower than non-Indigenous men.

The 11,900 Indigenous men who are classified as cultural workers have a median income of $40,800, 18% lower than non-Indigenous men.

The 15,400 Indigenous women who are classified as cultural workers have a median income of $41,200, also 18% lower than non-Indigenous men.

Notes on methods, including occupation lists

For census data, Statistics Canada notes that “Indigenous identity refers to whether the person identified with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who identify as First Nations (North American Indian), Métis and/or Inuk (Inuit), and/or those who report being Registered or Treaty Indians (that is, registered under the Indian Act of Canada), and/or those who have membership in a First Nation or Indian band.”

Census data are less complete for Indigenous Peoples than many other groups, which might result in a low estimate of the number of Indigenous artists (and other Indigenous workers). Some reserves and settlements did not allow census activity within their borders, while other areas were inaccessible due to wildfires or floods in the spring of 2021. Statistics Canada estimates that 23% of the on-reserve Indigenous population did not respond to the long-form census, a non-response rate that is almost 10 times higher than in the general population (2.6%). The response rate was likely higher for Indigenous residents off-reserve than on-reserve. I did not request separate data for off-reserve and on-reserve residents.

In order to ensure confidentiality and data reliability, this article presents only those statistics based on 40 or more people.

The income statistics in this post relate to 2020, a year with many pandemic lockdowns and slowdowns in artistic activity. It was also a year when many artists and cultural workers received support from pandemic assistance programs, including the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). It is impossible to know whether the lockdowns and slowdowns in artistic activity or the CERB payments had a greater impact on the differences in median incomes between artists and other workers. In theory, if the CERB payments had a greater stabilizing effect on incomes than the artistic shutdowns and slowdowns, it would have the effect of decreasing the income gaps between arts workers and other workers in 2020.

Statistics Canada’s full occupation titles for the 10 occupation groups included as artists are:

Actors, comedians, and circus performers

Artisans and craftspersons

Authors and writers (excluding technical writers)

Conductors, composers, and arrangers

Dancers

Musicians and singers

Other performers (including buskers, DJs, puppeteers, face painters, erotic dancers, and many other entertainers)

Painters, sculptors, and other visual artists

Photographers

Producers, directors, choreographers, and related occupations

The five arts leadership occupations are:

Conductors, composers, and arrangers

Conservators and curators

Library, archive, museum, and art gallery managers

Managers in publishing, motion pictures, broadcasting, and the performing arts

Producers, directors, choreographers, and related occupations

The statistics on workers in arts, culture, and heritage occupations include people who work in 52 occupation groups, including:

Heritage occupations such as librarians, curators, and archivists

Cultural occupations such as graphic designers, print operators, editors, translators, architects, and professionals in fundraising, advertising, marketing, and public relations

The occupational perspective counts people who work across the economy, as long as they are classified into one of the selected occupation groups. The analysis relates to professional workers, but with a very specific concept of professional. Census data on occupations include people who worked more hours as an artist than at any other occupation between May 1 and 8, 2021, plus people who were not in the labour force at that time but had worked more as an artist than at another occupation between January of 2020 and May of 2021. Part-time artists who spent more time at another occupation in May of 2021 would be classified in the other occupation. (The same would be true of workers in arts leadership occupations and all cultural occupations.)

A list of the 52 cultural occupation groups is available in my post from May 18, which also outlined the methods behind choosing these 52 occupation groups. In a post on April 18, I highlighted some strengths and limitations of the census for counting artists and cultural workers.