Long-term employment trends for artists and arts and culture workers

Rare bird alert! Today, I’ll delve into 25-year trends in arts and culture employment – back to 1997. This type of long-term analysis is extremely rare in the Canadian arts sector.

This post follows last week’s start to the series on arts and culture employment and self-employment, with posts about the situation in 2021 and pandemic-induced changes.

Tomorrow, I will examine recent and long-term trends for women in the arts and culture.

Today, I’m bringing artists back into the analysis, because a February report that I prepared only touched on these longer-term trends.

My analysis of long-term employment trends shows that, between 1997 and 2021:

There has been consistent growth in hours worked by all arts and culture workers over the long term, with the notable exception of 2020.

For artists, hours worked have risen and fallen through the years, with no consistent pattern. The pandemic resulted in a huge decrease in hours, but there was a rebound in 2021.

Hours worked by self-employed workers (of all kinds) have had a bumpy ride over the long term.

There has been a consistent increase in hours worked by employed arts and culture workers and all Canadian workers but a much less consistent trend line for employed artists.

My first post with the Labour Force Survey (LFS) data offered lots of information about the strengths and limitations of the LFS. Three notes bear repeating:

This is a very “big picture” view. The definition of arts and culture workers includes 50 occupation groups, including heritage occupations (e.g., librarians, museum workers, archivists), cultural occupations (e.g., designers, editors, architects), and artists (i.e., performing arts creators and interpreters, visual artists, artisans, craftspeople, and writers). See this pdf file for details.

The LFS information is available only for the full group of 50 occupations, plus a subset of nine occupations (artists), not for other subsets or individual occupations. We cannot use this data request to understand differences in trends between workers in the arts, heritage, and cultural industries.

Hours worked provides one of the best indicators of changes over time, especially in a sector where self-employment is common. (Many self-employed people lose gigs – i.e., hours worked – when times are tough but may not technically lose their job.) As I’ve noted previously, 65% of artists and 28% of arts and culture workers are self-employed.

More detailed notes regarding strengths and limitations of the LFS are appended to this post.

For Statistical insights on the arts to be sustainable, we need many more paid subscribers. Please consider upgrading your subscription, and never miss a post — like tomorrow’s post on women in the arts and culture.

All types of workers

The data in the following graph indicate that there has been reasonably consistent growth in hours worked by all arts and culture workers over the long term, with the notable exception of 2020. Between 1997 and 2021, the total hours of arts and culture workers increased by 45%.

There was also fairly steady growth in the hours worked by all Canadians, except for the first year of the pandemic. Between 1997 and 2021, the total hours of all workers increased by 30%.

For artists, hours worked have increased and fallen through the years, with no consistent pattern. The pandemic resulted in a huge decrease in hours, but there was a rebound in 2021. Overall, the total hours worked by artists increased by 17% between 1997 and 2021.

As noted above, there was reasonably consistent growth in hours worked by all Canadian workers and by arts and culture workers. Similarly, the number of Canadian workers grew fairly consistently, resulting in a 38% increase between 1997 and 2021, which surpassed the growth in hours worked during the same timeframe (30%).

The number of arts and culture workers increased even more, by 56% between 1997 and 2021. This exceeded the growth in their hours worked (45%).

During the same timeframe, the number of artists increased by 28%, which is more than the 17% growth in their hours worked. It is interesting to note that the overall changes for artists are lower than for the other two groups, whether measured by hours worked or the number of workers.

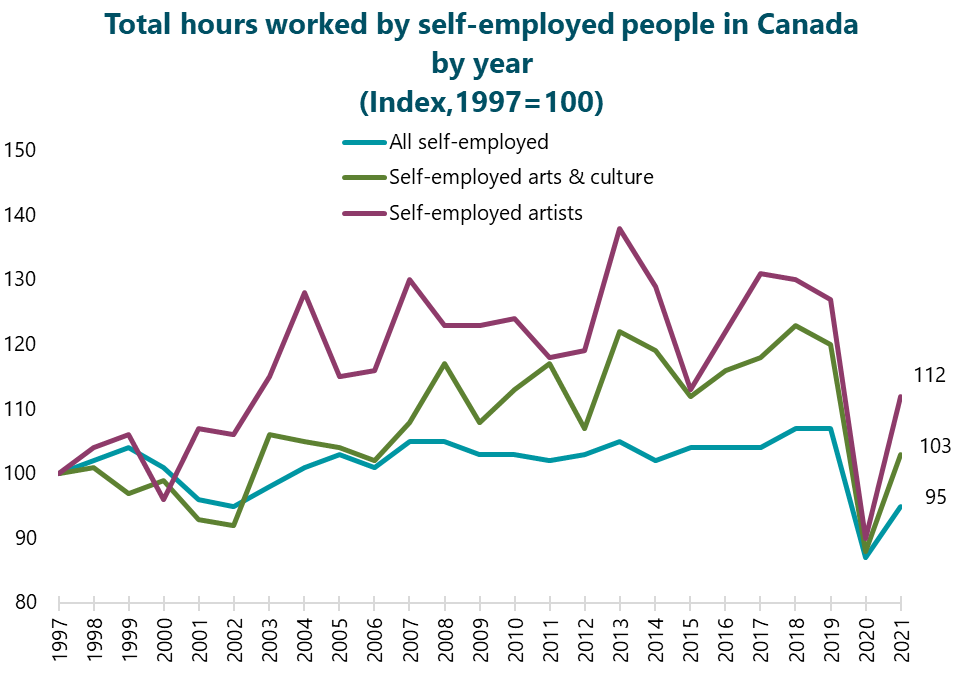

Self-employed workers

As the following graph shows, hours worked by self-employed workers (of all kinds) have had a bumpy ride over the long term. There was some growth in hours worked by self-employed artists, but the pandemic wiped out those gains. Between 1997 and 2021, total hours worked by self-employed artists increased by 12%.

There was more moderate growth in hours worked by self-employed arts and culture workers, which were also erased by the pandemic. Between 1997 and 2021, total hours worked by self-employed arts and culture workers increased by just 3%.

There was very limited growth in hours worked by all self-employed Canadians, and the pandemic reversed any gains. Between 1997 and 2021, total hours worked by self-employed Canadians decreased by 5%.

For all three groups of workers, the increase in the number of self-employed people exceeded the change in their hours worked between 1997 and 2021:

Self-employed artists: 28% increase in their number (vs. 12% growth in their hours worked).

Self-employed arts and culture workers: 30% growth in their number (vs. 3% increase in their hours worked).

All self-employed workers: 14% increase in their number (vs. 5% decrease in their hours worked).

Employed workers

The final graph in this post shows that there has been a consistent increase in hours worked by employed arts and culture workers and all Canadian workers between 1997 and 2021. There has been a much less consistent trend line for employed artists.

There was strong growth in hours worked by employed arts and culture workers, especially recently. Between 1997 and 2021, total hours worked by employed arts and culture workers increased by 66%.

There was more moderate growth in hours worked by all employed Canadians. Between 1997 and 2021, total hours worked by all employees increased by 38%.

Until recently, there was very little growth in hours worked by employed artists, with many decreases during the 25-year span. Hours worked have been below the 1997 level in 13 of the 24 years after 1997. Thanks to recent gains, however, total hours worked by employed artists increased by 24% between 1997 and 2021.

For all three groups of employees, the increase in the number of workers was similar to the change in their hours worked between 1997 and 2021:

Employed arts and culture workers: 69% growth in their number (similar to the 66% increase in their hours worked).

All employees: 43% increase in their number (similar to the 38% increase in their hours worked).

Employed artists: 21% increase in their number (similar to the 24% growth in their hours worked).

For readers who like their information in a table format, here is a summary of the key findings from this data analysis.

Note on the need for better tracking of arts work

For my thoughts on the need to better track the work of artists, please look back at my concluding remarks in a February report.

Notes about using the Labour Force Survey to understand the arts and culture workforce

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) provides timely and accurate estimates, particularly for employed and unemployed workers in the overall labour force, where monthly data are available and reliable.

Given the relatively small sample size of the monthly survey (56,000 households), data on smaller population groups have higher margins of error. To counter this limitation, my analysis focuses on annual averages (not monthly data).

The definition of “arts and culture workers” here is broad but consistent with Statistics Canada’s definition of the culture sector labour force and Hill Strategies’ previous work. 50 occupation groups are included as “arts and culture workers”. This includes heritage occupations (e.g., librarians, museum workers, archivists), cultural occupations (e.g., designers, editors, architects), and artists (e.g., musicians, visual artists, writers, actors, dancers) (See this pdf file for a list of all 50 occupation groups.)

In the broad occupational view in this post, arts and culture workers are not strongly concentrated in arts and culture industries. Rather, they work in a wide range of industries. Based on the detailed data available in the 2016 census, the most common industry groups for these workers are:

Professional services: 24% of arts and culture workers, including many architects, photographers, designers, and other creative professionals (industry code 54)

Information and cultural industries: 19% of arts and culture workers, including librarians and other library workers, film and TV managers and technicians, journalists, as well as producers and directors (industry code 51).

Arts, entertainment, and recreation: 12% of arts and culture workers, including many artists as well as managers, curators, and technicians in museums and art galleries (industry code 71)

Manufacturing: 9% of arts and culture workers, including printing press operators and other publishing workers, textile patternmakers, many industrial designers, as well as quite a few artisans and craftspeople (industry codes 31-33)

The LFS information is available only for the 50 occupations as a group, not for subsets or individual occupations.

Other important limitations of the LFS:

It captures data on Indigenous workers only every three months and only started capturing data on racialized workers in the summer of 2020. Given the relatively small sample size, I included very limited demographic information in my request.

People’s description of their main job during the reference period is used to classify them into occupations. Some data on secondary occupations is available but is not covered in this report.

The questionnaire captures salaries only, not self-employment earnings. Because of this limitation (and the high proportion of self-employed arts and culture workers), I did not include income data in my custom request.

No data are available for 2SLGBTQIA+, D/deaf, and disabled workers.

The Canadian census is a more robust source of information, including intersectional information and data on self-employment incomes. However, the census only takes place every five years.

Neither the LFS nor the census can provide insights into the reasons behind statistical trends, such as why and how certain groups of workers have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.