Local arts and culture workforce trends

Part 1: Six CMAs with populations over 1 million

Based on readily available occupation statistics from the Labour Force Survey

Since June, I have tried to ensure that my posts offer a lot of provincial analysis alongside nationwide statistics.

I have been searching / hoping for local data that would be both interesting and reliable. I think I’ve found something that fits the bill.

In a series of posts, I will analyze local statistics on the number of artists and select cultural workers in Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) across the country, using data from 2006 to 2021.

Today, I’ll focus on the 6 largest CMAs, each of which have a population over 1 million: Calgary, Edmonton, Montreal, Ottawa-Gatineau, Toronto, and Vancouver.

For comparison purposes, I’ll also analyze the Canada-wide averages.

Over the next two weeks, I’ll provide a similar analysis for 13 other CMAs: Halifax, Hamilton, Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo, London, Quebec City, Regina, Saskatoon, St. Catharines-Niagara, Sherbrooke, St. John’s, Victoria, Windsor, and Winnipeg.

Data source strengths and limitations

These posts are based on publicly available occupation statistics from the Labour Force Survey (LFS). The LFS has a sample size of 56,000 households each month.

The data are imperfect, but I’ve done a lot of behind-the-scenes number crunching to see whether I think that we can trust the information. My answer: a qualified yes.

“Qualified” because data on smaller population groups have higher margins of error. Like my June analysis of Canadian data, these posts will focus on annual averages in order to provide a higher level of statistical reliability.

Still, some local estimates have significant swings, even on an annual basis. Some of these swings might be real (such as decreases in arts and cultural work in 2020), but others might be due to a lower quality of estimate in a given year. I analyzed the fluctuations in every CMA with data back to 2006 and selected 19 CMAs that had a low enough standard deviation (before 2020) and enough workers to provide confidence in the data.

Smaller grouping: artists and (select) cultural workers

Statistics Canada offers the dataset with summary groupings of occupations, with the key one being “occupations in art, culture, recreation, and sport” (which I’m calling “artists and select cultural workers”).

The categorizations do not provide enough detail to follow the standard definition of artists and cultural workers (i.e., the 50 occupations groups listed in this pdf file). The data are therefore partial, when compared with my previous analyses of cultural workers.

The dataset provides a breakdown of “occupations in art, culture, recreation, and sport” into two sub-groupings, but these are less likely to be reliable on a local basis: “professional occupations in art and culture”; and “technical occupations in art, culture, recreation, and sport”.

Cultural workers account for most workers and most occupations in the summary grouping of “occupations in art, culture, recreation, and sport”:

28 of 33 occupations are cultural workers, including all 9 artist occupations. Based on 2016 census data for Canada, cultural workers account for 72% of all workers in this grouping, including the 28% represented by artists.

The standard definition of cultural workers that I’ve used previously has 50 cultural occupations. The 28 occupations that are in the LFS grouping represent just over one-half of all cultural workers (55%).

The 5 non-cultural occupations represent 28% of all workers in this grouping (based on 2016 census data). The largest non-cultural occupation is “program leaders and instructors in recreation, sport, and fitness”.

Earnings data are not available in the summary dataset published by Statistics Canada. For the cultural sector, this is not a big loss, because the LFS questionnaire captures salaries only, not self-employment earnings, and therefore won’t provide enough detail to estimate the earnings of artists and cultural workers.

Why analyze this dataset, rather than the census, which has a larger sample size?

The strengths of this data are timeliness and easy availability.

The Labour Force Survey is conducted monthly, but the local estimates would not be reliable on a monthly basis. However, when multiplied by 12, the sample sizes become more interesting.

The annual averages from the Labour Force Survey can show us trends that the census, conducted only every five years, cannot. (Also, occupation data from the census is published roughly a year and a half after the census is conducted. We are still waiting for labour force data from the census in May of 2021.)

This dataset is readily available and offered to anyone who wants to access it, although it does help to have experience with Statistics Canada datasets to retrieve only the information that is most relevant. Local cultural workers could download the data themselves.

Focus on broad trends

Given the Labour Force Survey’s limitations, I will stick to some broad trends among the grouping of artists and cultural workers.

The analysis that follows is relatively simple: has the number of artists and cultural workers (in the key occupation grouping) increased or decreased? What hints can we glean about pandemic-era trends in each CMA from recent data?

Trends for the 19 CMAs as a group

Between 2006 and 2021:

17 of the 19 CMAs saw an increase in the number of artists and select cultural workers.

The increase in the 19 CMAs was well above the Canadian average. The median increase was 22% in the 19 CMAs, compared with an overall increase of 8% in Canada.

Among the six large CMAs in this post, the increase was largest in Edmonton.

Canadian data

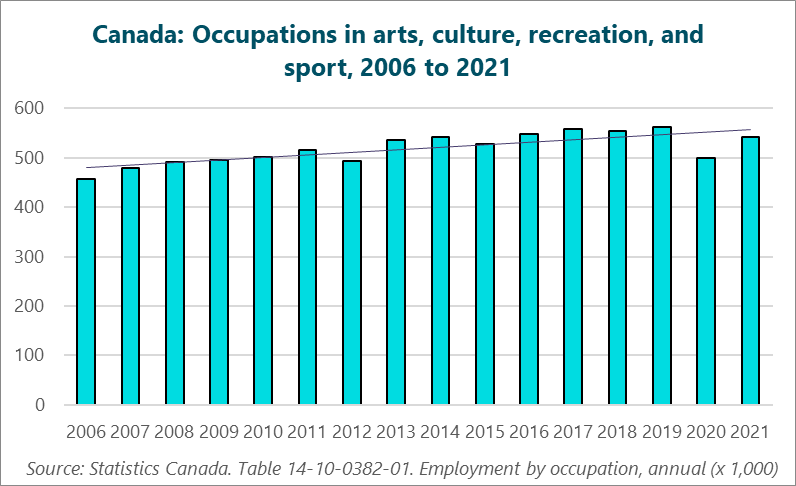

The first graph shows nationwide data for each year, plus a linear trend line. The vertical axis is in the thousands (roughly 450,000 to 550,000). However, I will not focus on the raw numbers, mostly due to the grouping of occupations that is imperfect for our purposes. (As noted above, cultural workers represent about three-quarters of all workers in the available grouping, and the available grouping represents just over one-half of all cultural workers.)

Here is what I see in this graph:

The increasing trend line indicates that the number of workers in the key grouping of artists and select cultural workers has been on the rise. There was a significant drop in 2020, and the 2021 estimate remained below the estimates for 2016 through 2019.

Details for each of the six large CMAs follow.