Economic impacts of the arts and culture in Canadian provinces and territories: A longer-term view

One province and one territory saw a real per capita increase in their cultural economies between 2010 and 2020, despite the pandemic. Others saw pre-pandemic growth only.

The key question that I investigate this week is: In which Canadian provinces and territories did the cultural economy increase or decrease between 2010 and 2020? I’ll also look at pre-pandemic changes, i.e., 2010 to 2019. The analysis follows last week’s post related to pandemic-specific changes (2019 to 2020 only).

Data for the most recent year (2020) of Statistics Canada’s Provincial and Territorial Culture Indicators were released on June 2, and 2010 is the first year of comparable data.

This post highlights two measures of longer-term changes in the economic impacts of the arts, culture, and heritage:

Gross Domestic Product (GDP, or direct economic impact, a measure of net value-added to the economy). The GDP statistics have been adjusted for inflation and population growth to provide an estimate of real per capita growth or decline.

Jobs (including both full-time and part-time positions, not on a full-time-equivalent basis)

“Arts, culture, and heritage” includes (in descending order of GDP impact in Canada in 2020):

audiovisual and interactive media

visual and applied arts

government-owned cultural institutions (which are excluded from other areas)

written and published works

live performance

heritage and libraries

sound recording

education and training

Almost all the statistics in this post have been adjusted for both inflation and population growth in each province and territory. These are sometimes referred to as real per capita changes. The inflation adjustments are based on estimates of changes in the Consumer Price Index in each province and in the capitals of the three territories. Like population changes, the inflation adjustments vary between jurisdictions.

See the notes at the end of this post for further explanations and definitions.

In Canada, longer-term changes in the direct impact of the arts, culture, and heritage between 2010 and 2020 included:

An 8% decrease in impact on GDP after adjusting for inflation and population growth. (This was a 21% increase before the inflation and population adjustments, which shows how significant the adjustments are over the full timeframe.) The entire GDP decrease came in the first year of the pandemic: there was essentially no change between 2010 and 2019 (-0.1%), but there was an 8% drop in 2020 (adjusted for inflation and population growth).

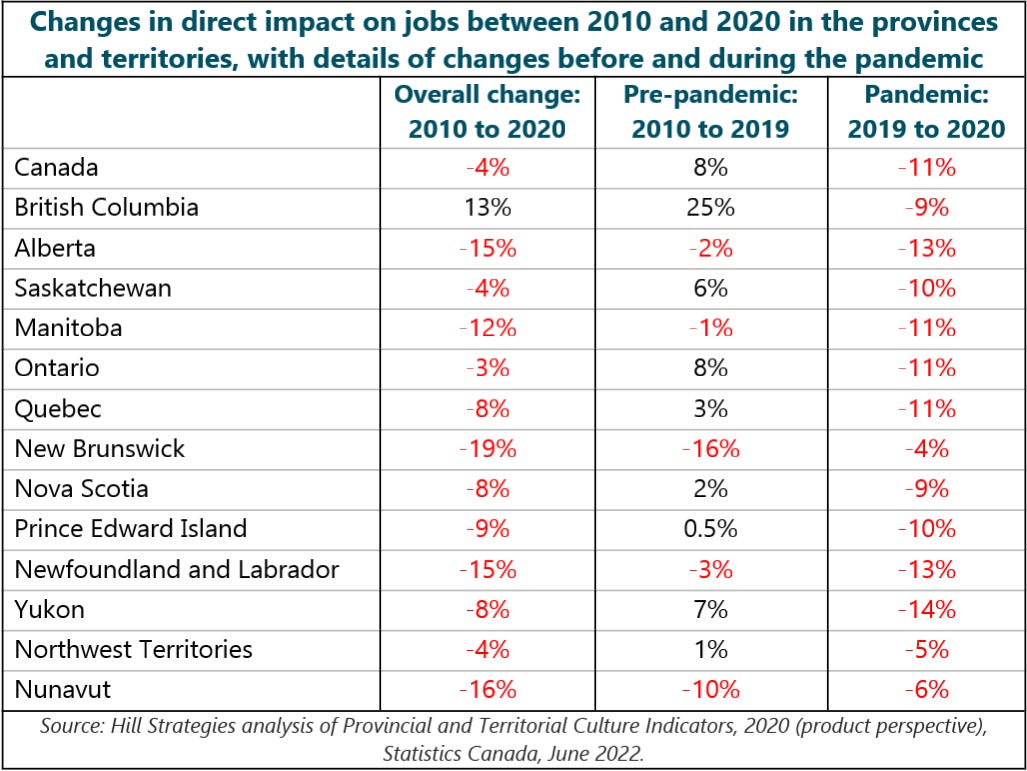

A 4% decrease in cultural jobs: As was the case with GDP, the reduction in jobs came in 2020 (-11%), negating an 8% increase between 2010 and 2019.

This post explores the similarities and differences in these changes across the country.

Similarities between jurisdictions

The cultural economy was severely impacted by the pandemic in every province and territory.

The number of cultural jobs decreased in every province and territory – except one – between 2010 and 2020.

Differences

In some provinces and territories, the cultural economy’s direct impact on GDP increased between 2010 and 2019 (the year before the pandemic).

In many others, the direct impact on GDP had decreased between 2010 and 2019, and then decreased further in 2020.

This post groups the provinces and territories in three ways: primarily by the change in direct impact on GDP between 2010 and 2020 (the “overall” period); secondarily by the change before the onset of the pandemic (i.e., 2010 to 2019); and finally, by changes in 2020.

Stick with me: there are a lot more numbers in today’s post. I hope that it’ll be worth your time and effort to follow along. I’ve boldfaced the first mention of each province and territory for ease of reading / skimming.

British Columbia and Nunavut: Growth in cultural GDP despite pandemic decreases

B.C. and Nunavut were the only two jurisdictions where there was real per capita growth in GDP between 2010 and 2020.

GDP growth was 4% in B.C. and 3% in Nunavut, after adjusting for inflation and population growth. (The increases were 40% and 43%, respectively, before the adjustments, which shows how significant the adjustments for inflation and population growth are over the decade.)

In B.C., the adjusted growth rate of 4% between 2010 and 2020 includes an 11% real per capita increase before the pandemic, followed by a 7% decrease in 2020.

B.C. was the only jurisdiction where the number of cultural jobs increased between 2010 and 2020. The province’s 13% increase was the result of a 25% increase between 2010 and 2019, followed by a 9% decrease in 2020.

In Nunavut, the 3% real per capita growth in GDP between 2010 and 2020 includes a 4% real per capita increase before the pandemic, followed by no change in 2020.

Before the pandemic, the number of cultural jobs in Nunavut decreased by 10%, followed by another 6% drop in 2020, for an overall decrease of 16% between 2010 and 2020.

Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador: Pre-pandemic growth erased by the pandemic

In three provinces (Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador), there was a real per capita increase in the direct economic impact of the arts, culture, and heritage between 2010 and 2019, but these increases were reversed in 2020.

Ontario’s cultural economy decreased by 3% between 2010 and 2020 after adjusting for the province’s inflation and population growth. Before the pandemic, Ontario’s cultural economy saw a real per capita increase of 4%, followed by a 7% decrease in 2020.

Similar to the change in GDP impact, the number of cultural jobs in Ontario increased before the pandemic (by 8%), only to decrease significantly in 2020 (-11%), resulting in a 3% decrease between 2010 and 2020.

In Nova Scotia, the adjusted change between 2010 and 2020 (-4%) includes a 5% real per capita increase before the pandemic and an 8% reduction in 2020.

The number of cultural jobs in Nova Scotia increased slightly before the pandemic (+2%) but decreased by 9% in 2020, for an overall 8% decrease between 2010 and 2020.

Before the pandemic, Newfoundland and Labrador’s cultural economy eked out a 0.4% real per capita increase in its impact on GDP between 2010 and 2019. However, a 7% decrease in 2020 led to an overall decrease of 6% between 2010 and 2020.

A pre-pandemic decrease in cultural jobs in Newfoundland and Labrador (-3%) was followed by a 13% reduction in 2020, resulting in an overall loss of 15% between 2010 and 2020.

Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, and Quebec: Single-digit pre-pandemic decreases exacerbated by the pandemic

In three jurisdictions (the Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, and Quebec), the pandemic added on to relatively small real per capita decreases in the direct economic impact of the arts, culture, and heritage between 2010 and 2019.

In the Northwest Territories, the cultural economy decreased by 5% between 2010 and 2019, followed by a 2% decline in 2020, resulting in an overall decrease of 7% between 2010 and 2020.

A small 1% increase in cultural jobs in the Northwest Territories between 2010 and 2019 was followed by a 5% decline in 2020, resulting in an overall loss of 4% between 2010 and 2020.

Saskatchewan’s cultural economy decreased by 7% between 2010 and 2019 and by the same percentage in 2020, for an overall decrease of 14% between 2010 and 2020.

Before the pandemic, the number of cultural jobs in Saskatchewan increased by 6%, only to decrease significantly in 2020 (-10%), resulting in a 4% decrease between 2010 and 2020.

In Quebec, a 6% real per capita decrease in GDP impact between 2010 and 2019 was followed by a 9% reduction in 2020, for an overall decrease of 14% between 2010 and 2020.

The number of cultural jobs in Quebec increased somewhat before the pandemic (+3%) but decreased by 11% in 2020, for an overall 8% decrease between 2010 and 2020.

Prince Edward Island, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Yukon, and Alberta: Significant pre-pandemic decreases in economic impact, and then the pandemic hit

The five other provinces and territories experienced double-digit decreases in the direct economic impact of their cultural sectors between 2010 and 2019. The pandemic aggravated these decreases.

Prince Edward Island’s cultural economy decreased by 12% between 2010 and 2019 and by another 5% in 2020, for an overall decrease of 17% between 2010 and 2020.

In PEI, there was essentially no change in cultural jobs between 2010 and 2019 (+0.5%), but the pandemic brought on a 10% reduction in 2020, resulting in a 9% decline overall between 2010 and 2020.

The 12% real per capita decrease in Manitoba‘s cultural economy between 2010 and 2019 was followed by a 7% decline in 2020, resulting in an 18% decrease between 2010 and 2020.

A small 1% decrease in cultural jobs in Manitoba between 2010 and 2019 was followed by a substantial 11% reduction in 2020, resulting in an overall loss of 12% between 2010 and 2020.

In New Brunswick, an 18% real per capita decrease in GDP impact between 2010 and 2019 was followed by a 3% decrease in 2020, for an overall drop of 20% between 2010 and 2020.

The number of cultural jobs in New Brunswick decreased substantially before the pandemic (-16%) and by another 4% in 2020, resulting in the largest decrease in cultural jobs among the provinces and territories between 2010 and 2020 (-19%).

Yukon’s cultural economy decreased by 17% between 2010 and 2019 and by another 6% in 2020, resulting in a longer-term decrease of 22% between 2010 and 2020.

Before the pandemic, the number of cultural jobs increased by 7% in Yukon. However, Yukon was the worst hit jurisdiction by the pandemic in terms of cultural jobs (-14%), which led to an overall reduction of 8% between 2010 and 2020.

Alberta experienced one of the largest real per capita decreases in its cultural economy between 2010 and 2019 (-16%), followed by the largest decrease in 2020 (-12%). This resulted in the largest overall reduction in culture GDP among the provinces and territories: -26%.

The number of cultural jobs in Alberta decreased by 2% between 2010 and 2019 and by another 13% in 2020 alone. This resulted in a significant 15% drop in cultural jobs between 2010 and 2020.

Data tables

Notes and data sources

Statistics Canada defines culture sector GDP as:

The economic value added associated with culture activities. This is the value added related to the production of culture goods and services across the economy, regardless of the producing industry. Culture jobs are the number of jobs that are related to the production of culture goods and services.

Six main areas (called “domains” by Statistics Canada) are included in the calculations:

Live performance (including performing arts as well as cultural festivals and celebrations, excluding government-owned organizations, which are captured in “governance, funding, and professional support”.)

Visual and applied arts (including architecture, advertising, crafts, design, and works of art)

Written and published works (including books, newspapers, periodicals, and other published works)

Audiovisual and interactive media (including broadcasting, film and video, and interactive media, excluding government-owned organizations, which are captured in “governance, funding, and professional support”)

Sound recording (and music publishing)

Heritage and libraries (including non-government-owned libraries, archives, cultural heritage, and natural heritage. Government-owned organizations are captured in “governance, funding, and professional support”.)

Also included are three supporting domains:

Governance, funding, and professional support (including, among other items, all government-owned cultural venues, which are therefore not counted in other areas, e.g., heritage and libraries, live performance, visual and applied arts, etc.).

Education and training (including cultural programs offered at educational and training establishments)

Multi domain (including items that could not be allocated to a specific domain)

An estimate of the value added of the arts (i.e., separate from other cultural and heritage elements) is not possible from the data, because many of the above areas include elements that could be included in the arts, culture, and heritage. For example, “visual and applied arts” might sound like a domain that would fit well in the category of “arts”, but it includes architecture, advertising, and design, three subdomains that are not typically included in the arts.

The data capture direct impacts only and are therefore relatively modest. Excluded are commonly measured elements such as indirect impacts (the re-spending of the expenditures of cultural organizations) and induced impacts (the re-spending of wages earned by cultural workers and suppliers’ workers). Despite the smaller numbers, there are benefits to the narrower approach: the estimates are comparable between jurisdictions and to the GDP of other sectors of the economy.

This post analyzes Statistics Canada’s estimates of the impacts of culture products, i.e., the production of culture goods and services from establishments in both culture and non-culture industries. (See Culture and sport indicators by domain and sub-domain, by province and territory, product perspective (Table 36-10-0452-01).)

Statistics Canada also provides another set of estimates, on culture industries, which captures the production of culture and non-culture goods and services from establishments within the culture industries.

In 2020, the national culture products estimate ($56 billion, or $1,460 per capita) was 9% lower than the industries estimate ($61 billion, or $1,604 per capita).

For the real per capita calculations, population data were drawn from Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex, Statistics Canada Table 17-10-0005-01. Inflation in each jurisdiction was sourced from Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted, Statistics Canada Table 18-10-0005-01.